CSL Brill 188 is southbound on Central Ave at North Ave, with a westbound streetcar in the background on North Ave. You can see that trolley buses shared wire on North with streetcars– an unusual occurrence in Chicago, although it was common in other cities. Photo courtesy the Illinois Railway Museum Strahorn Library and the Scalzo collection, caption help courtesy of Roy Benedict.)

Chicago Trolley Buses and Shared Wire

One of our readers recently brought our lead photo (from http://www.trolleybuses.net) to our attention:

Very good example of streetcars and trolley buses using a shared wire in Chicago. Not very common here.

My first thought was that this picture may have been taken in 1949, when CTA switched route 72 – North Avenue from streetcar to trolley bus.

North Avenue was converted to trolley bus between the west end and North and Clybourn in 1949. A streetcar shuttle continued between Clybourn and Clark until they extended the line to Clark with the loop by the Chicago Historical Society (now the Chicago History Museum).

The photo is not dated, so I can’t comment about what was going on at the time that it was taken. I only mentioned it because shared wire was not common in Chicago unlike other cities (i.e. Milwaukee). I believe that the CSL logo is on the Brill trolley bus, but we know that CTA was slow to apply their decals on various surface vehicles in their early years so it could be a 1949 photo. I believe the conversion was in December 1949.

I looked up the conversion date on http://www.chicagorailfan.com and they give it as July 3, 1949. Having done additional research, it looks like the photo is most likely from the CSL era after all.

This enlargement (below) of part of a 1946 CSL supervisor’s map shows that trolley buses could run west on North Avenue from the garage at Cicero all the way to Narragansett, where they could then turn north. (The solid lines are streetcar routes, the dashed lines trolley buses, and the others represent gas buses.)

I am sure that most Chicago transit historians don’t know of that shared wire for 2 miles. In the past the only shared wire that I knew about was on Chicago Avenue from Larrabee to Halsted, a very short distance in comparison to what existed on North Avenue.

If you study those maps you might find other examples of shared wire.

Looking at this map, the shared wire on North Avenue was probably a matter of necessity in 1930, when CSL’s first trolley bus routes began service on Chicago’s northwest side. I suppose there was little choice but to string wire on two miles of North Avenue to connect the barn with these routes, even though North Avenue was not yet served by trolley coaches. It probably helped tip the scale in favor of the later conversion, since they had already done part of it.

Trolley buses ran on Narragansett between 1930 and 1953, when the line was consolidated with the one mile extension of the North Avenue route. Rather than extend wire to North and Harlem, CTA substituted gas or propane buses on all of route 86. (By then, Cicero Avenue was likely the preferred means of moving trolley buses north and south from the North Avenue garage, so Narragansett was superfluous.)

Starting in 1949, the 72 trolley bus used the wire between Narragansett and Cicero that had presumably been put up in 1930.

Interestingly, in 1959 Oak Park village officials wrote to the CTA requesting extension of trolley bus service on North Avenue between Narragansett and Harlem Avenue. While I have not read CTA’s reply, they probably said no funds were available for such an extension. By 1959, it would seem that a decision had already been made to gradually phase out trolley bus service as the fleet aged and reached the end of their service lives (although some of these buses ran for many additional years after 1973 in Mexico).

It would seem that 1958 was the pivotal year for CTA to decide that it was going to eventually do away with all surface electric vehicles. It probably was a subtle decision because of course the focus had been on the removal of streetcars entirely by 1957/1958. After the streetcars were gone, they came to the realization that a lot of the overhead infrastructure and substations would have to be upgraded to maintain trolley buses indefinitely. Always being the ones to cut costs without any concern for the environment except in the use of propane buses, CTA sought to trim everything to the best of their ability. It is interesting how different their approach was to surface electric transit than that of the Toronto Transit Commission which was already going full speed ahead with the building of subways while at the same time retaining streetcars and trolley buses.

I think that you can pretty well establish the beginning of the end of the trolley bus era in Chicago when the streetcar wire on 79th Street and Halsted was taken down, I believe in 1958. Both lines had been converted to motor bus in the early 50s, but the overhead wire was kept up with the anticipation of converting them to trolley bus. Andre Kristopans, the source of unbounding transit trivia, might be able to tell you when those wires were finally taken down. Unfortunately, I did not take any photos of the wire on Halsted, but I do have photos of the 79th Street wire at Vincennes/79th where the Clark-Wentworth cars crossed 79th Street. CTA took out the crossing, but used the 79th Street wire to hold up the streetcar wire at the crossing on Vincennes.

The 1951 DeLeuw, Cather and Company consultant’s report for CTA recommended against buying any more electric surface vehicles, due to the high cost of power purchased from Com Ed. As it happens, CTA entered into a new 10-year contract with Com Ed in 1958, which went into effect just after the last streetcar ran. The rate was a small increase over the prior agreement.

One possibility is that the trolley buses were kept until they were fully depreciated. CTA got the streetcars off the books before they were fully depreciated through their PCC Conversion Program, where 570 of the 600 postwar PCCs were sold to St. Louis Car Company for scrapping and parts reuse in a like number of rapid transit cars.

These issues are discussed in detail in our E-book Chicago’s PCC Streetcars: The Rest of the Story, available in our Online Store. You will also find CSL/CTA supervisor’s track maps from 1941, 1946, 1948, 1952, and 1954 in the same publication, along with the complete text of the 1951 DeLeuw, Cather consultant report and much more.

An enlargement from a 1946 CSL supervisor’s map shows how streetcars and trolley buses had two miles of shared wire between Cicero and Narragansett.

More Grand and Nordica

FYI, we’ve added these two photos of trolley buses near Grand and Nordica to our recent post Chicago Surface Lines Photos, Part Five:

This image from http://www.trolleybuses.net, credited to the Scalzo collection, shows a Grand trolleybus, Marmon 9437, at Grand and Nordica on October 12, 1968. There was a grocery east of the loop, which later became a thrift store.

Marmon 9437 westbound on Grand at Newland on September 7, 1969, again from http://www.trolleybuses.net and the Scalzo collection. From 1954 to 1964, my family lived just south of here on Medill. The Rambler dealer later became AMC, then Jeep, Chrysler-Jeep and is now demolished. We are a short distance from the Grand-Nordica loop.

Thomas Wozniak writes:

Thank you for sending out your very informative DVD so fast. I’m really enjoying all the history and rare photos that are included in it. I wish there were more photos of the construction of the Congress St. Expressway and the dismantling of the West Side, Humboldt Park, Kenwood, Stock Yards, and Normal Park branches. Did you work for the CTA?

No, I never worked for the CTA, although I certainly have used it a lot my entire life. I guess I will just have to remain an “Ownerider,” thanks.

However, we have already posted lots of pictures of the Metropolitan and Garfield Park “L”s, as well as the construction of the Congress rapid transit line, on the previous blog we were involved with. You can use keyword searches to find those posts.

Chicago CB&Q Suburban Stations

Charlie Vlk writes:

While I am a CB&Q researcher I do have interest in Chicago Traction, having worked at All Nations Hobby Shop with “Traction Ted” Seifert and knew George Trapp, Joe Diaz, Rich Boszak, George Clark, Bob Kutella and other customers “back in the day”.

I am researching pre-1900 CB&Q Chicago suburban stations. I have shots of Millard Avenue/Shedd Park and Crawford Avenue. I would like an image of the Douglas Park Station and am hoping it might show up in construction photos of the Douglas Park “L” bridge over the Q or maybe during the track elevation raising of that bridge.

I am also interested in the Chicago (14th Street) Union Avenue, Ashland, Blue Island, and Western Avenue and Panhandle Crossing stations that existed before track elevation. Perhaps some of these were adjacent to streetcar lines and show up in pictures?

PS- I used to ride the North Shore Line from Milwaukee to Chicago and would connect with the Bluebird bus to Brookfield, 31st, and Prairie to get home on weekend leave from St John’s Military Academy 1958-1963. Of course, I never took even one picture in those five years!!!

You might find the attached pdfs from the Chicago Tribune about the Suburban Railroad and Chicago, Hammond & Western disputing their crossing at the Brookfield/La Grange Park border interesting.

Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1897

Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1897

We’ll see what our readers might know, thanks.

Book Review

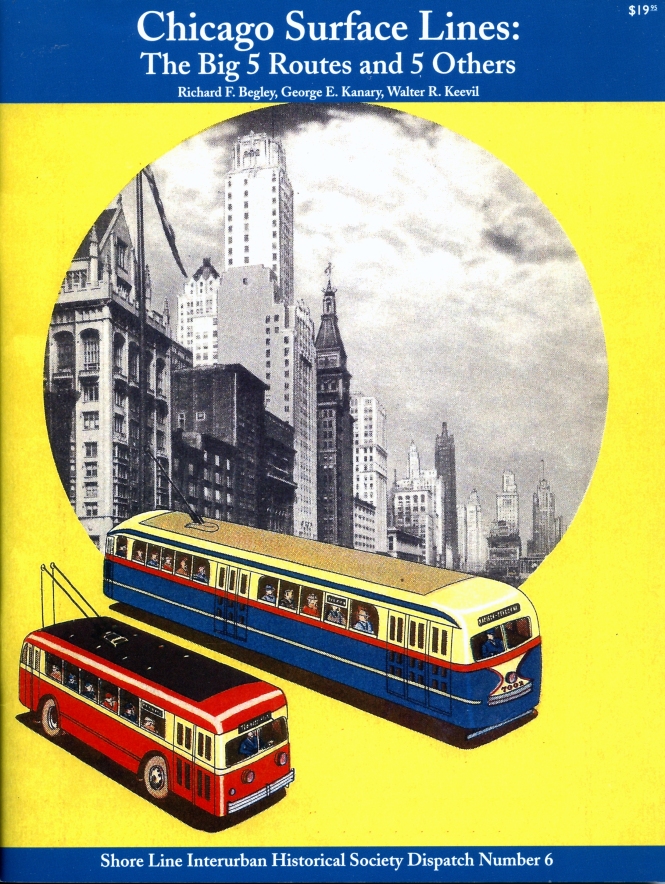

Chicago Surface Lines: The Big 5 Routes and 5 Others

by Richard F. Begley, George E. Kanary, and Walter R. Keevil

Dispatch Number 6 of the Shore Line Interurban Historical Society

While I certainly do appreciate full-length railfan books, I am also very much in favor of shorter ones, such as this new 100-page volume from the Shore Line group. The Chicago Surface Lines is a vast subject, since it was, in its heyday, the largest and most extensive street railway system in the world. Here, the focus is on the five biggest CSL routes, plus five small ones.

This book is a welcome addition to the admittedly slim shelf of Chicago streetcar tomes. The three authors are all very experienced, and their reputations precede them. They are that rare combination, being both gentlemen as well as scholars.

While there is a goodly amount of informative text herein, for most readers, the main interest will be in the photographs, almost all of which are in classic black-and-white. The overall format should be familiar to anyone who has read previous CSL articles in First & Fastest, Shore Line’s quarterly magazine. If the result here seems like several such articles strung together, there’s nothing wrong with such an approach. I have enjoyed those articles too.

As far as I know, most of the pictures here have not previously appeared elsewhere. Many are from collections acquired by the authors over the years, and are reproduced from the original negatives, often from film formats larger than 35mm. The photos themselves are excellent, as is the quality of their reproduction.

The general approach is not altogether different from our own CSL posts. Naturally, in our case, when we get things wrong, our readers help point out these mistakes (sometimes within a few hours) and we make the necessary corrections.

In the case of a printed book, such an approach is impossible. Everything needs to be corrected and fact-checked ahead of time. Since the authors are seasoned veterans of this sort of thing, the chance of finding any factual errors is very slim indeed.

Of course, the three authors have an advantage in years over this writer. They experienced many of these things first-hand, while we merely strive to learn about them after the fact. We are doing our best to educate ourselves and get caught up.

There is value in both approaches, the permanence of a book, and the immediacy of a blog.

Any criticisms I might make would be very minor in nature and would seem like nit-picking. I won’t even bother mentioning them.

It’s safe to say that anyone who appreciates seeing Chicago streetcar pictures on this blog would also like this book, which is available directly from Shore Line using the link given above. It is highly recommended.

-David Sadowski

PS- Please note that Trolley Dodger Press is not affiliated with the Shore Line Interurban Historical Society.

Help Support The Trolley Dodger

This is our 109th post, and we are gradually creating a body of work and an online resource for the benefit of all railfans, everywhere.

You can help us continue our original transit research by checking out the fine products in our Online Store. You can make a donation there as well.

As we have said before, “If you buy here, we will be here.”

We thank you for your support.

PS- As we approach our one-year anniversary this month, the deadline for renewing our premium WordPress account comes due in less than two weeks. This includes out Internet domain www.thetrolleydodger.com, much of the storage space we use for the thousands of files posted here, and helps keep this an ads-free experience for our readers. Your contributions towards this goal are greatly appreciated, in any amount.

2015 Annual Report

We thank our readers for making our first year such a success. We received 107,460 page views in all, from 30,743 individuals.

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2015 annual report for this blog.

Here's an excerpt:

The Louvre Museum has 8.5 million visitors per year. This blog was viewed about 110,000 times in 2015. If it were an exhibit at the Louvre Museum, it would take about 5 days for that many people to see it.

Click here to see the complete report.

The back cover of Shore Line Dispatch Number 6.

Does anyone know when CSL/CTA began to equip streetcar trolley poles with graphite slider trolley shoes which replaced the trolley-pole wheels. One prerequisite for the graphite sliders was a necessity, and that was the use of grooved or fig. 8 overhead wire which provided a smooth, uniform under running electrical contact surface. Many systems had replaced trolley wheels in the late 1920s as Milwaukee did in 1929. Philadelphia replaced the trolley-pole wheels on its remaining streetcars in the late 1970s! The wheels were old-fashioned frequently arcing and sparking as it rolled on the wire underside sometimes making a squealing noise.

Here’s a link to the 2016 annual CTA on-line historic calender.

November 2016 features one of the first pre-war first generation PCC cars mistakenly noted as one of 88 instead of 83 new cars.

http://www.transitchicago.com/assets/1/miscellaneous_documents/15JD_072_historic_calendar_2016.pdf

can you please change this: streetcars in the 1970! to this:streetcars in the late 1970s!

I fixed it, thanks!

Fixed-equipment costs probably weren’t the only consideration the CTA had when they began phasing out trolley buses. My step-grandfather was a bus mechanic at the North Avenue garage, and he told me that they had two separate groups of maintenance personnel, one for the engine-powered buses (propane and diesel) and one for the electrics. Add that to the need to upgrade the distribution system (including putting the feeders underground to protect against ice storms), and the trolley buses days were numbered.

If their days were numbered, why do other cities, such as Boston, Seattle, Philadelphia, etc. continue to run them? Trolley buses were popular in Chicago, in part because the public perception was that they offered a higher quality service.

CTA Board Member Werner W. Schroeder, in his Metropolitan Transit Research study (mod-1950s) concluded that trolley buses were the most profitable form of transit that CTA offered. You can read the entire report in my E-Book Chicago’s PCC Streetcars: The Rest of the Story, available via our Online Store.

There is also the environmental argument. If trolley buses had survived here until the gas crisis hit (it started in October 1973, about six months after the system was abandoned) chances are it would have been kept.

I think it was the funding structure the CTA was built on. Not enough money for all the fixed assets so streetcars and trolley buses went away, as well as marginal portions of the L. The death blow for trolley buses has been said to be the 1967 Big Snow, and the only reason that they hung on until 1973 was the inability to get more diesel buses in a short time. There may be other reasons we are not aware of that have kept trolley buses going in other cities, but not in Chicago. All I remember of them is that they seemed to be in shabby shape compared to the diesel buses. We may see other electrical buses here though. in the future.

The CTA is experimenting with battery-powered buses.

Regarding infrastructure, in the 1950s the Chicago Transit Board was told that the savings realized through elimination of streetcars involved the older, red cars that were operated by two men. It was a savings in labor cost.

When red car service ended, they were also informed that no additional savings would be realized through elimination of the PCC streetcars. There are reasons for thinking quite the opposite happened.

Fast, modern streetcars were replaced by much slower, ponderous propane buses that had difficulty maintaining their schedules. CTA also stated, in both 1954 and 1957, that elimination of streetcars and their tracks made the streets more hospitable to cars and trucks, and actually produced more traffic congestion, leading to further ridership losses on transit.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the decade from 1948 through 1957, when streetcars were eliminated, was also the period when the CTA surface system suffered its worst ridership losses, nearly 50% in all.

Streetcars were not the only factor in this, of course. There was the rise in automobile ownership, adoption of the 40-hour work week, and numerous fare increases as well.

The 1951 DeLeuw, Cather consultant report stated that it might actually cost CTA more to replace the PCCs with buses than it would to keep them. Instead, it recommended converting all the cars to one-man.

The infrastructure on the PCC lines, according to this report, was in good shape.

In addition, CTA could have purchased many additional one-man PCC cars on the used market in the 1950s for very little money, as other cities did, such as Toronto.

Milwaukee’s Trackless Trolley Cars, to the riding public in Milwaukee they were as elsewhere known simply as trolley buses, trackless trolleys or just plain buses.

But to The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Co they were always known, promoted and advertised as trackless trolley cars, the stops on the routes they were used on were always signed as Car Stop as opposed to Bus Stop.

Where trackless trolleys shared stops with diesel and/or gas buses these stops were always indicated as Car Stop and Bus Stop.

The reason for this arrangement was that Wisconsin Electric Power and its subsidiary TMER&LCo. had won concessions in the early 1930s from the state’s automotive licensing bureau to recognize the trackless trolley as a vehicle captive to “tracks in the air”. Just as streetcars were captive to tracks in the pavement and required no license plates, the trackless trolley also was to legally exempt from licensing requirements, in accidents and such the vehicle’s company serial number would suffice for record purposes.

While doing research for Chicago’s PCC Streetcars: The Rest of the Story, I found a couple newspaper reports from 1950 indicating that Chicago streetcars did not have to follow automobile speed limits. Doubtless CSL or CTA may have imposed speed restrictions of their own in various places, but if the auto speed limit was 30mph and a PCC went 40mph, the police could not give the operator a speeding ticket.

You might expect that traffic congestion was more of a problem for streetcars, but there were reports of PCCs going very fast indeed when they could do so.

I suspect that one “savings” was the reduced cost of a pair of 6000’s by recycling PCC streetcar hardware, but that begs to question: why didn’t the CTA buy up more PCC streetcars to be reborn as additional 6000 series rapid transit cars. The 4000’s could have been retired earlier, and it’s always good to have extra rolling stock. I guess we’ll never know.

In Chicago’s PCC Streetcars: The Rest of the Story, I break down the various costs and benefits of CTA’s PCC Conversion Program. First of all, despite various statements made over the years claiming a savings of $22k or $25k for each PCC so scrapped, the amount CTA actually received for each car from St. Louis Car Company was $14k. Then, you would have to deduct from this the cost of modifying the controllers for use in rapid transit cars. This was $3k per car. Then, there were other costs involved in refurbishing the parts that were recycled, which were used when the program began in 1953 and were even more used by the time the last streetcar ran in 1958.

CTA estimated that the cost of refurbishing parts ate up all of their savings by the time the program ended. Therefore it should be no surprise that the final 26 or so streetcars on the property at the end of 1958 were simply sold to a scrap dealer. No parts were salvaged. (Fortunately, we can be glad that one car, the 4391, was saved.)

The additional costs involved in the program were simply rolled into the cost of the new cars made by St. Louis Car Company. They were not broken out, and therefore remain hidden costs. But it is certainly true that the cost of each of the various 6000s orders was an increase over the previous order, and likely more than the amount of inflation at the time.

These orders were placed via a bid process where there was only one bidder, the St. Louis Car Company. Pullman had bid on the original 1952 order for 100 cars, but there bid was high and that contract was cancelled the following year, when it was found there were unexpected difficulties in adapting these parts. It had to be put out for re-bid.

On top of that, CTA estimated that a PCC car was worth 1.5 buses. The 600 PCCs had to be replaced by 900 buses. Streetcars were estimated to have a useful life of 20 years, and buses only 12 years. The average cost of a bus during the 1950s was in the range of about $19-20k. So, the cost of the replacement buses was certainly several times the actual amount of any savings from scrapping the postwar PCCs and recycling their parts. Meanwhile, CTA could have purchased additional one-man PCCs from other cities at prices that have been estimated at $3-5k, much less than the cost of buses.

As I wrote in my E-book, the conversion program only made sense of you consider that streetcars were worthless, which of course, they aren’t. Other cars of approximately the same age as Chicago’s are still being used in service in a few cities. Those cities don’t consider them worthless.

One reason why CTA did not purchase other PCCs just to recycle the parts is that the program made no economic sense. In my humble opinion, its main benefit was to take the PCCs off the books far in advance of their depreciation.

Simply put, the Chicago Transit Authority decided in 1952 that it did not want to continue operating streetcars, and this program was the fastest way of getting rid of them, while claiming there was a positive value involved. It was often claimed that so much money was saved through the program that it paid for the cost of a replacement bus. Obviously, this cannot be true.

In addition, if CTA had to replace a one-man PCC with one and a half buses, that meant an actual increase in labor costs.

Therefore, it should be no surprise that in 1954 CTA told its board not to expect any additional savings from the elimination of streetcars.

Without the conversion program, chances are the fate of the Chicago PCCs would have been similar to Chicago’s trolley buses. They would have continued using them until at least 1966-68, by which time the cars would have been 20 years old and fully depreciated.

Interesting thought, PCC’s running to the late 60’s in Chicago. Of course, then they’d have run afoul of the Big Snow in 1967.

I’d always heard when I was younger that the reason streetcars survived in other cities in the US was that they were running on medians, like Stony Island Avenue, but wondered why then the Stony tracks had been pulled up. My observation as a traffic engineer was that some streets were too narrow for streetcars, and overhead wires for both streetcars and trolley buses would have made it difficult to use mast arm-mounted traffic signals. Just an observation.

[…] the Comments section of a recent post, Jeff Weiner and I corresponded about the CTA’s PCC Conversion Program, a subject also […]

The blurb for “Chicago Surface Lines: The Big 5 Routes and 5 Others” begins as follows:

“In 1931, the five largest Chicago Surface Lines routes, in terms of originating revenue passengers, were Ashland, Clark-Wentworth, Halsted, Madison and Milwaukee. The combined riding on these routes was greater than the total riding in many medium-sized American cities. CSL also had some very small routes in terms of ridership and they demonstrate the diversity of CSL’s operations.”

Does anyone have, or know where to find, a list of annual ridership statistics for individual CSL / CTA lines?

CSL (and other streetcar companies) did compile such statistics, no doubt about that. However, much information of this type (for US systems in general) has been lost or destroyed. Any information or “leads” re. CSL would be greatly appreciated.

Perhaps you can look at the yearly reports issued by the Board of Supervising Engineers during the CSL era?