Kenneth Gear, author of today’s post, has long been a friend of this blog. Since we began writing about William A. Steventon and the Railroad Record Club of Hawkins, Wisconin (see our previous posts A Railroad Record Club Discography and Revisiting the Railroad Record Club), Ken has been very helpful in obtaining recordings in our quest to reissue the entire RRC oeuvre for the digital age.

Recently, following up on a lead for some RRC material, Ken traveled from New Jersey to the Midwest. The discoveries he is sharing with you today are the result.

This represented a tremendous investment of time and money for Ken who, like myself is of very modest means. Since there is only a very limited market for railroad audio (the whole world, apparently, being transfixed with video), chances are we will never be able to recoup Ken’s costs.

He does not care about that, since his main interest is in preserving these historic recordings for future generations. Ken is doing this for the love of it, not the money.

Thanks to Ken, we will now be able to reach our goal of remastering all 41 issued Railroad Record Club recordings onto compact discs. We will let you know when that work is done. The only ones we don’t have now are some of the samplers.

One unexpected benefit of his quest is the discovery of additional unissued steam and electric RRC recordings, detailed below.

Due to the limits of Ken’s budget, he was unfortunately not yet able to purchase what appear to be the original RRC master tapes. If you are interested in making a contribution to that worthwhile effort, please let us know.

Any donations received will help Ken negotiate for their purchase, and make it possible to preserve these fine recordings for future generations of railfans. They are currently at risk of being lost forever.

It is remarkable that this collection somehow managed to stay intact for 24 years after Steventon’s death.

We thank you in advance for your help.

-David Sadowski

PS- The disc labeled Indiana Railroad is actually Steventon reciting a history of the Hoosier interurban. Since it quit in 1941, that predates the development of audio tape recorders in the early 1950s. A few fans had wire recorders in the late 1940s (these were developed in Germany prior to the war). Prior to that time, the only way to make a “field recording” was with a portable disc cutter. Those were available starting around 1929.

My Railroad Record Club Treasure Hunt

by Kenneth Gear

Some months ago David received a very intriguing email. It came from an estate auctioneer who wrote that he was in possession of a large collection of items from the estate of William Steventon, founder of the Railroad Record Club. He had seen the Trolley Dodger CDs for sale online and figured David would be interested in the collection. The auctioneer had these items in storage, where they had been for many years, and he now wanted to dispose of them. He asked David if he would be interested in buying these items or if he knew of anyone who might.

Knowing my keen interest in all things related to the RRC, David forwarded the email to me.

We were quite excited about the offer. What could this collection consist of? Had we hit the mother lode of RRC material? The possibilities were almost endless- photos, art work, even movies! The most satisfying find for me would be, of course, coming across some unreleased Steventon railroad audio. If there were some, would the 60 plus year old tapes be salvageable? Were they stored properly? As endless as the possibilities for great finds were, it was equally possible that disappointment could lie ahead.

At the very least it seemed very likely that we would be able fill the holes in the Trolley Dodger CD reissuing catalog. We were still in need of records 22, 31 & 32 plus the elusive sampler records.

Emails went back and forth between the three of us and eventually concrete plans were hammered out.

My friend and fellow railfan photographer Chris Hughes and I usually make several road trips a year in pursuit of short line railroads to photograph. This year, and as a favor to me, it was decided to find some photographic subjects conveniently close to were the Railroad Record Club items were stored. I wasn’t going to let this opportunity slip by without at least seeing the collection. On July 20th Chris and I set off from New Jersey heading for the Midwest, some short line RRs, and the possibility of a RRC gold mine!

The Day Arrives!

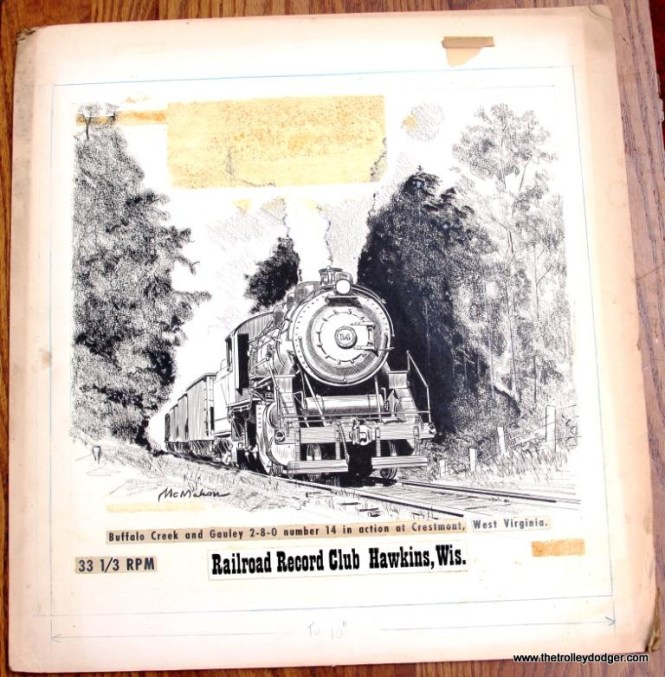

Anticipation was running high as I approached the building that housed the collection. Some of the items were laid out on a table and there were large boxes containing many copies of the same record, all still sealed in plastic and all were the 12″ reissues editions. What immediately caught my attention was that each box had beside it the metal print block for the cover of the LP contained in the box. There were other print blocks on the table as well, not every one had a box of LPs to go with it. This was the real deal for sure. Where else would the original print blocks come from but the Steventon estate.

I wanted the print blocks but was less interested in buying the LPs. I really didn’t want to get saddled with scores of records that I would have to find a place to store and later try to sell. A deal was struck and I got the print blocks but not the LPs. So far so good.

Next up was what appeared to be Mr. Steventon’s personal collection of RRC albums (for some unknown reason number 23 was missing). The records were in plain white jackets and did not have any of the liner notes or cover art with them. Just a hand written number in the upper right hand corner of the jacket, corresponding to the record contained therein. The records were a mix of 10 and 12 inch stock. It could be that Steventon upgraded his own collection with the 12″ remasters as they were pressed and that the 10″ records in his collection never got the 12″ treatment. If true, then we can finally know exactly which of the records were reissued and those that were not. It seems likely, but we will need to look a little deeper into this. Interestingly a few of the plain white jackets have a hand written “delete schedule” on them. This I’m sure is some whittling down of the tracks to fit in the allotted time of the record. Photos of two of them follow. Also found was a sampler record. I always thought there were 6 of these records but it turns out that each year only has one side of a disc. Therefore it’s not 6 records, but only 3. 1 down and 2 to go.

Along with these LPs came a large stack of test pressings. I wasn’t sure of just what may be on them, perhaps the deleted audio written of in those delete schedules. They went into the back of the SUV with Steventon’s personal RRC records. Things were getting very interesting!

The stack of test pressings consisted of 44 12″ records from the Nashville Record Productions and 4 10″ pressings from RCA Custom Records.

Also, I saved perhaps 50 10″ empty record jackets that were heading to a dumpster. I’m glad I did because I was able to find the jackets for 22 BC&G, 31 Sound Scrapbook-Steam & 32 NYC. I got those records from Steventon’s personal collection, but they did not, as I said, have any liner notes or jackets with them.

So no more suspense- yes unreleased Steventon railroad audio was indeed found!

It came in the form of “Audiodisc” record blanks that Steventon cut at home. For convenience’s sake, or perhaps to keep his tapes safe, he transferred field recordings on to these “record at home” discs. 25 of these discs were offered to me and I snatched them right up. Later at home, I discovered that 21 have railroad sounds on them. The rest were radio shows and a relative who was apparently proficient at playing the piano.

These discs are 10″ and play at 78rpm. They contain about 6 minutes of audio when fully utilized but not all are. Frustratingly some records, in spite of the label being marked “Western Maryland” or “Pennsylvania RR”, are blank on one side or contain just a fraction of the audio it could hold. There is plenty of good stuff here and the condition of most of the records are surprisingly good in my opinion. Here are some of the highlights:

One of the best finds is a record marked “B&O-1st Recording” It seems I have found a record of William Steventon’s first recordings! From the article he wrote for TRACTION & MODELS we know he accidentally erased his very first recording of a B&O steamer while trying to play it back. So perhaps this is actually his second attempt. The record contains B&O steam & Diesel sounds recorded at the station in Riverdale, MD on March 31, 1953. Trains include number 523 “Marylander” and number 17 “Cleveland Night Express” among others.

He would return to the B&O many times, with recordings being made at both Riverdale and Silver Springs, MD. I have records of B&O trains recorded in July, August, and September 1953. Some of these recordings include the station announcements for trains number 9 “Chicago Express” and Train 5 “Capitol Limited” . There is one great sequence (too short) of an on-train recording behind B&O 5066 powering local train #154. Also there is a very good recording of a 5300 series loco on a heavy drag freight. Even early on he sure knew how to capture the sound of steam.

There are recordings of steam on the Shenandoah Central (loco # 12) IC # 3619 at Christopher, IL, PRR at Mill Creek, PA, C&IM, and on the EBT. Some of this material may have been included on the released albums, but here William Steventon himself provides commentary and the sounds may be edited differently. Steventon gives information about almost every cut in his distinctive, Walter Winchell-like voice. Other interesting sounds are those of PRR GG-1s recorded on August 22, 1954. They were recorded at, as Steventon puts it, a “country crossing”. Plenty of that toneless yet somehow appealing GG-1 horn blowing is included.

Potomac Edison box motor # 5 has several sides of these records devoted to it. Without checking, I’d say there is more of the sounds of the cab ride on these discs than what eventually made it on to Record #6. There is some Shaker Heights RT as well. Plenty of Johnstown Traction and Altoona & Logan Valley too. This may or may not have been released.

There is definitely some unreleased traction sound here. One full record contains the sounds of the Baltimore Transit company. One side is a ride on car # 5727 on the Lorraine Line and the other side is car # 5706 on the Ellicott City Line. Both recorded on January 16, 1954 This recording is in wonderful shape too.

More fine unreleased traction sounds include a nice recording of the St. Louis Public Service. Recorded in December of 1953 it includes both on board and trackside recordings of PCC cars on the University Line.

There is also some Washington DC Capital Transit stuff I don’t think made it to Record 27.

There are some unidentified traction sounds on an unmarked disc. The record starts with William Steventon telling a story about a blanket someone gave his father that had pictures of locomotives on it (his father was an engineer on the NYC). The story abruptly ends without concluding and the sounds of motor hum, gears, and door buzzers start. It sounds to me as if the recording was made at a subway station. We know Steventon made recordings in the IRT subway in New York and this may very well be it. The other side has more unidentified traction sound that may been the Queensboro Bridge recordings that were mentioned in the RRC newsletter David posted in this blog some time ago. Maybe someone knows for sure what all this sound really is. One other record worth noting is titled “Claude Mahoney.” Playing the record reveled that he was a radio commentator in the Washington DC area. This is both parts of a two-part show about riding an NRHS fantrip from Washington DC to Harrisburg, PA by way of Hagerstown on October 4, 1953. No train sounds are included but it is interesting in itself, especially if you enjoy old time radio broadcasts.

All of these records will soon be sent off to David for him to transfer to digital. Hopefully he can clean up and restore some of the sounds that right now, are degraded with surface noise and various clicks, pops, and hisses. I’m sure there is enough good sound to fill out a CD and it sure will make a great Railroad Record Club “bonus tracks” CD.

Another interesting aspect of the Railroad Record Club story is that some years after William Steventon’s death in 1993, his son Seth made an effort to reissue the entire RRC catalog on cassette tapes. David and I made inquiries about this to several people without much success. It’s likely the project was abandoned before much headway was achieved.

Evidence of Seth’s attempts were included in the estate. All of the records were converted to cassette and cover art and liner notes were put on cards for every record. Four completed tapes were in the collection and so are many of the cards.

Next I purchased 10 cover art paste-up boards. These are what was used to make the print blocks. A few actually contain the original art work. It seems Steventon would have the lettering glued to the same canvas board that the artist drew the picture on. They are not all originals, but several are. This was a bit of luck I would have never thought possible. On a few, such as the BC&G drawing for number 22 and the trolley picture for #23, the glued-on lettering has fallen off. This has revealed more of the drawing than we record owners have ever seen.

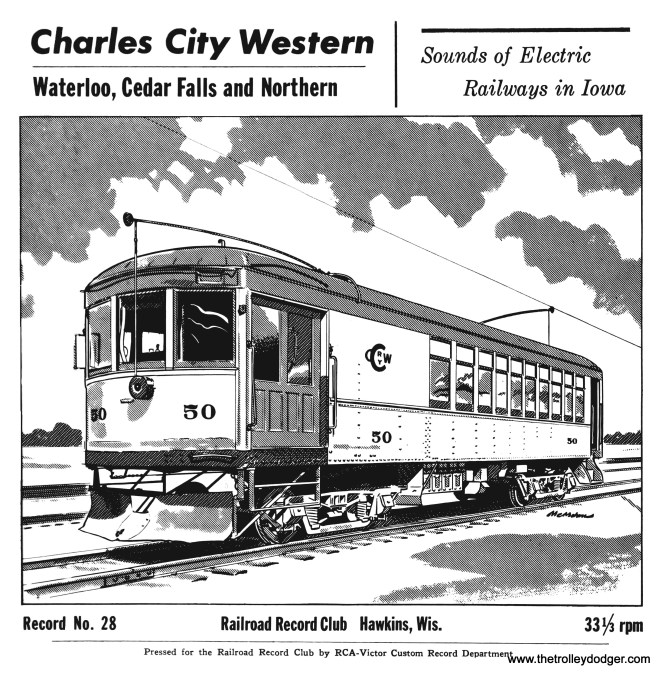

One other original drawing was found hiding among the others. It is of WCF&N interurban car # 100. This drawing did not appear on any RRC record jacket. The car is featured on Record 2. The first edition of the record had a cover that featured a photograph of the car. The second edition had a drawing of it, but it is not the one I have. Both of these editions were on 10″ stock. There is no way of knowing for sure but maybe a 12″ reissue of number 2 was in the works and this was to be the cover illustration. It’s possible. It could also be that this was a gift to Steventon or he commissioned it simply because he liked the car. Who knows?

Several boxes of photos were for sale as well. Both finances and cargo space were starting to reach their limits so I had to choose only a few to buy. As time allows I will scan and email all of the photos to David and he can include them in future Trolley Dodger posts. For now, I’ve scanned a few photos that in some way relate to the Railroad Record Club.

Photo 1. I was looking for a good photo of William Steventon, preferably in a railroad setting or with audio equipment in the field or at home. Nothing was found but this photo of him I think is quite good.

Photo 2 & 3. I found a copy of the photo that was used in the TRACTION & MODELS magazine article, the one that shows him making a recording of a North Shore Line interurban car. It has been posted in this blog before but this is a much better scan. It was made from an actual photograph and not a magazine reproduction as posted before. The shot is somewhat wider too. Because it is a good scan it is possible to crop the photo to a point where you can get a good look at all that recording equipment he needed. Imagine having to cart all that stuff around. Think of this next time you shoot audio AND video on your tiny Smartphone!

Photo 4. As was stated before, William Steventon’s father Seth was an engineer on the Big 4 (New York Central). This is very likely him in the cab of NYC 6879. Photo is dated 1915.

Photos 5 & 6. These two are good photos to keep in mind while listening to Record # 20 C&IM/NYC. The in cab recording Steventon made while aboard NYC # 1441 with his father as engineer was recorded while switching in this yard. While this photo was not taken at the time the sound recording was made (sound recording made December 9, 1953, these photos were taken on February 12, 1948) and is of a different locomotive (NYC # 1169), the setting is the same- the yard at Cairo, IL. In the liner notes of this record Steventon writes about the sound of the locomotive being “amplified by the huge empty lumber shed we were paralleling at the time.” That huge empty lumber shed is plainly visible in the wider shot of # 1169. Seth was again the engineer at the throttle.

Photo 7. Seth in the cab of Shenandoah Central # 12. This is the locomotive that is on one of the unreleased audiodisc records. It was very likely taken on the same day as that the sound recordings were made.

Photo 8. When I saw this picture in the box with a bunch of others, it stood out to me. Why I wasn’t sure until I took a closer look. It is of Charles City Western car # 50. What made it stand out was that the angle and position of the car is exactly as the car appears on the cover of record 28. Remove the car barn and some of the background, take away the bit of freight car to the left, add a few clouds in the sky and you have the record cover! It would be hard to convince me that the record cover drawing is not based on this photo.

Photo 9. CCW car 50 as it appears on RRC record # 28’s cover. Compare the two.

A few interesting documents were found as well. There was a large box of correspondence to and from the Club. Apparently Mr. Steventon threw very little away. If you ever wrote to him or ordered a record from him, chances are your letter or envelope are in that box! I looked briefly for anything from me but no luck. I would have needed more time to do a good search.

What I left Behind

There were more treasures to be found in that darkened building for sure. Time, storage space, and money, the bane I’m sure of every collector, shook me from my excitation. No more space and no more money meant no more discoveries.

While I’m very happy with what I got, there is still more. All those boxes of records I turned down and all those wonderful photos I couldn’t afford. I would hate to find out they had to be trashed.

The most glaring oversight on my part were the boxes of reel to reel tapes I saw. I did look at them and even took some photos, but it all appeared to be master tapes for the records. All these sound I was positive were safely cut into vinyl.

After getting home and closely looking at those photos I can now see that there was unreleased railroad audio there too. Such titles as L&N, NKP Diesel, IRT Subway, IND Subway, 3rd Avenue El and the Queensboro Bridge Trolley, among others, now jumped out at me. Perhaps there might be a way to save this material as well.

I had a great time making these discoveries, and I’m very happy that David should be able to make CDs of these sounds so they can be shared with all who are interested. After not being heard in decades, it feels great to be a part of the effort to bring these lost Railroad Record Club sounds into the light of day.

Recent Correspondence

Continuing from our last post (regarding Speedrail) Larry Sakar writes:

This was the aftermath of the 8/24/49 collision at Soldiers Home. Car 1143 with motorman Ralph Janus was an all steel car. That was the one that backed up. Car 1119 with motorman LeRoy Equitz was a car that was wood with I think steel sheets surrounding it. That was true of nearly all of the 1100-series TM single cars except 1142-1145. Those 4 were all steel. Equitz was speeding going twice as fast as he should have been given that he had a yellow caution signal. As you came downhill and into the Calvary Cemetery cut, the r.o.w. made a sharp curve beneath the Hawley Rd. overpass and then continued downhill. That and the Mitchell Blvd. overpass at the east end of the cut limited the view ahead. Equitz didn’t spot the 1143 until it was too late.

The newspaper picture I’m attaching looks forward from the front or what was left of the front of 1119 to the back of 1143. Note the telescoping. That’s the floor of 1143 in front of the fireman who is bending over on the right. Had anyone been sitting in the smoking compartment of 1143 they would have been killed. Luckily, no one was.

The Calvary Cemetery cut is the only part of the abandoned r.o.w. that remains relatively unchanged today. Here are some photos of it over the years.

Thanks for sharing!

Larry again:

Here’s more about that accident, Dave as well as a view of the 65 as it looked upon arrival in Milwaukee. Note no front end “LVT” design.

I promised Scott (Greig) that I would look into the Speedrail accident of 9/5/50 to see if the newspaper accounts identified the crew of car 1121. In the July, 2017 comments, Scott thought that the motorman of car 1121 was Ralph Janus who was motorman of car 1143 which backed up for the missed passenger at Soldiers Home station on 8/24/49 and was rammed from behind by car 1119 with motorman LeRoy Equitz. I thought it was someone by the name of Eugene Thompson.

According to the Milwaukee Journal article, “Speedrail Dead Now 10; Line Has New Collision” (MKE Journal 9/5/50 P.1) the motorman of car 1121 was Eugene Thompson. The motorman of car 64 which 1121 ran into was Virgil McCann. There was one passenger aboard car 64, Ewald Rintelmann, age 50 of Hales Corners whom the article says was “shaken and bruised.” I hoped that the other two crew members aboard car 1121 would be identified but they weren’t. It only mentions that there were “2 other men aboard the freight car.” At least not in this article or the following day. As I mentioned previously, I recall the late Speedrail motorman Don Leistikow saying it was a father and son, one of whom was the conductor and the other the brakeman. The article reported that Maeder “initially blamed the accident on ‘slick, moisture covered tracks’.” The accident happened 1000 feet south of the West Jct. station.

The 9-5-50 article is also where we hear of the 8 or 9 year old boy Maeder saw “standing awfully close to the landing at Oklahoma Ave.,” who drew his attention away from the Nachod signal. “Ordinarily, you keep you eye on the light for more than an instant,” Maeder said. “On Saturday, however, I noticed a small boy about 8 or 9, standing awfully close to the tracks at Oklahoma av. landing. When I noticed, in a quick look, that I had the white light, my thoughts turned to the more immediate danger of the small boy and I turned my eyes from the light to the boy.”

I’ll give Maeder credit for coming up with a good story to explain his failure to keep an eye on the signal but that’s all. He makes no mention of the fact that Speedrail supervisor John Heberling was stationed at Oklahoma Ave. and that he had set the switch so that Maeder’s train went into the siding. Nor does he mention that he ordered Heberling to immediately reset the switch and let him out of the siding when the latter wanted to take time to call the dispatcher and see where Equitz was at. Neither John Heberling nor any of the fans gathered around Maeder on the front platform ever reported seeing a small boy playing or standing near the tracks.

When Maeder refers to “the landing,” I am guessing he was referring to the station platform. Oklahoma Ave. station was on the bridge over Oklahoma Ave.

About 3 years ago I had a phone conversation with George Wolter, the assigned motorman on Maeder’s train. I asked if it was true that Maeder took control of the train shortly after leaving the Public Service Building outbound to Hales Corners. He confirmed that Maeder said, “Go and have a seat. I’ll take it from here,” when they got to 6th & Michigan Sts. I asked if Maeder had given him a reason and he said, “Well we got caught in a traffic jam on 6th St.” I said, “OK but what does that have to do with anything?” Maeder taking over operation of the train wasn’t going to change the fact that you were caught in street traffic. I mean he wasn’t Moses. He couldn’t lift up his switch iron and demand that the traffic part and let his train pass in the name of the Lord.”

I know that was a rather sarcastic remark but Wolter’s excuse for Maeder was utterly ridiculous. Wolter said, “I will swear to my dying day that I saw that signal at Oklahoma Ave. and it was white.” That was the end of the conversation. His statement contradicts what he told the DA and testified to at the Coroner’s inquest. His exact statement at that time was that he was just coming up front having “gone back to the rear car for a while.”

This was when he spotted the roof of Equitz’s train coming up over the top of the hill ahead of the northbound train. He said he DID NOT see the signal at Oklahoma Ave.! I think his testimony at the time carries far more weight than the way he remembered events more than 60 years later. I should also point out that had he been so inclined the DA could have charged Wolter with negligence since PSC rules required that a qualified motorman had to be present at all times when someone who was not qualified was operating the train. He had absolutely no business being in the rear car of 39-40.

Don Leistikow said that had he been the motorman he would have stood right next to Maeder whether he liked it or not. He would have been the scheduled motorman and this was officially his train. He was the person responsible for it. As Don pointed out the PSC regulations did not make an exception just because you owned the company. Based on the way the DA went after Maeder and statements made by the DA as early as 9-5 when he said he had concluded that based on the evidence he’d gathered that Maeder went thru a red signal. And it was obvious that he wasn’t buying Maeder’s story about safety concerns. Maeder’s frequent sessions with railfans in his office, seeking their input while ignoring Tennyson the VP of operations, fits the pattern of someone who on 9/2 saw an opportunity to bask in the admiration of his fellow model railroaders and railfans and just couldn’t pass up such a “golden opportunity” to show off by being at the controls of duplex 39-40. Tennyson said as much in my book and reluctantly, I would have to agree with him.

I am sure our readers will appreciate this important bit of history on what was a very serious tragedy.

Finally, Larry asks:

One thing that has puzzled me for a long time is why the CTA was so anti-streetcar. It seems to me that they would have wanted to keep the PCC’s running on at least the 22-Clark-Wentworth, the 36-Broadway-State and the 49-Western Ave. Weren’t those 3 lines some of the busiest crosstown streetcar routes? It’s always seemed to me, not knowing much more than the basics about the CSL and CTA that it appeared to be terribly wasteful to junk all of those mostly new St. Louis Car PCC’s. Yes, I know that a lot of parts went into the 6000 series “L” cars but did they really recoup their investment?

I know there have been books written about the CSL but has anyone ever thought about writing a comprehensive history of it say for CERA? Dave Stanley told me that when CTA acquired CSL it was broke. Was the CRT in any better shape, financially?

In a way it’s too bad the CTA wasn’t selling off the PCC’s in 1949.Both the Waukesha and Hales Corners lines had turning loops so their being single ended would not have been a problem though whether Maeder could have afforded them, I have serious doubts.

TM did not have turning loops on any of the streetcar lines and that is part of the reason S.B. Way was not interested in buying PCC’s for Milwaukee. It would have meant constructing loops at the ends of the car lines or buying double ended PCC’s. I know of only 2 systems that had double ended PCC’s; PE and Dallas. Of course by the time the first PCC’s rolled off the production line for the Brooklyn & Queens, TM had pretty much turned its back on streetcars in favor of trolleybuses.

The Chicago Transit Authority purchased the Surface Lines in 1947 for $75m. However, the CSL had $30m in cash on hand in a renewal account, so the actual amount spent was only $45m.

While the underlying companies behind the CSL facade were bankrupt, this was more of a technical bankruptcy, a situation that the City of Chicago wanted to maintain since they had by the mid-1940s decided that municipal ownership was the only way forward. Otherwise, contemporary accounts indicate that CSL could have emerged from bankruptcy during WWII.

CSL could have done better, except that its fares were being kept artificially low by the Illinois Commerce Commission. When the CTA took over, there were numerous fare increases in its first decade of operation since the agency had the power to set its own rates.

By contrast, the Chicago Rapid Transit Company was a financial basket case that could barely pay its bills. During the transition to CTA ownership between 1945 and 1947, the most that CRT could spend for new railcars was $100k, while the Surface Lines had millions on hand for such purchases. CRT ordered four articulated sets while CSL ordered the 600 postwar PCCs plus other buses.

CSL was very much a pro-streetcar operator, but in the years prior to 1947, had been expanding service using motor buses and trolley buses, including some initial conversions of lightly-used streetcar routes to bus.

The City of Chicago commissioned a transportation study in 1937 that suggested replacing half the trolleys with buses. This still would have meant purchasing 1500 new streetcars.

As the years went on, this amount kept being decreased in the plans, from 1500 to 1000 to 800, and ultimately it became 600.

While the CTA still planned to order an additional 200 PCCs in their 10-Year Plan, published in 1947, this did not come to pass, and the first general manager of CTA, Walter J. McCarter, was hired in part because of his success in “rubberizing” the Cleveland streetcar system.

So, while CSL was pro-streetcar, increasingly the City of Chicago was pro-bus, and when municipal ownership came to be, the new CTA reflected the attitudes of the City.

The war had put off some bus substitutions and equipment purchases, so there was a backlog of conversions in the pipeline by that time. This led to a more rapid switch from streetcar to bus than might have been the case otherwise.

The difficulty in abandoning lightly-used lines also worked against CSL, and to some extent CSL and CRT competed with each other. Once CTA took over, they could rationalize both systems to work better together.

Still, even as late as 1949, CTA was at least considering purchasing 200 more PCCs, and retaining service on as many as 11 streetcar lines. The 600 PCCs were brand new, and the 83 prewar cars plus the 100 Sedans could have provided good service for many years to come.

Around that time, however, a number of factors were already at work against the surface system in general.

First, along with increased car ownership and frequent fare increases, there was a serious drop-off in surface system ridership, to the point where it was eventually decided that buses could do the job.

Second, the CTA changed its method of accounting, allocating a portion of surface system revenue to the rapid transit. This meant that some service that were once considered profitable were suddenly seen as unprofitable.

One thing that CTA did almost immediately was work to reduce their labor costs by eliminating as many employees as possible. This became even more important in the inflationary postwar period as unionized workers demanded better pay and benefits. CTA had a chronic manpower shortage and was thus in a weak position to hold the line.

Since most streetcars were two-man, they were easy targets for substitution by one-man buses.

A 1951 consultant’s report proposed that CTA retain the PCCs, convert them to one-man, and stop purchasing electric vehicles for the surface system due to the supposedly high cost of electric power purchased from Commonwealth Edison.

By the 1950s, CTA had become convinced that maintaining ridership was a matter of providing faster service. Faster service could not easily be provided on city streets, with increasing competition from cars and trucks, but there were ways to speed up service on the rapid transit system.

The so-called PCC Conversion Program was mainly public relations. The CTA had decided it no longer wanted to operate streetcars, yet had 600 that were just a few years old, with an expected 20-year life and attendant depreciation. The main purpose of the program was to take these cars off the books in a way that would not show a loss on paper.

While frequent claims were made that supposedly the program was yielding $20,000 or more per streetcar, CTA actually received $11,000 for each of the 570 cars sold to St. Louis Car Company. In addition, there were thousands of dollars in additional costs involved with adapting and reconditioning parts. Over the five years or so of the program, the amount of costs increased, to the point where, by 1958, CTA admitted it was receiving no more than scrap value for each PCC sold.

But since these were non-standard cars, there was no market for reselling them to another city.

The Conversion Program only made sense if you believed that PCC streetcars, which were state-of-the-art and just a few years old, had absolutely no future value as transit vehicles, even though the 1951 consultant report indicated that the tracks and wire were in good shape and were worth keeping. The consultant thought that the cost of replacing the service with bus was more than the cost of keeping what they had.

CRT was in such bad shape that within a few short years, CTA decided to devote 70% of its investments in upgrading it, even though in 1947 it only had a market share of less than 20% of local ridership. As a consequence, some might argue that the surface system got the “short end of the stick,” especially after October 1, 1952 when CTA purchased the assets of the competing Chicago Motor Coach Company.

Perhaps not coincidentally, this was also the date when the CTA, having eliminated its last remaining competitor, announced the Conversion Program that spelled the end of streetcars in Chicago. It was no longer necessary to offer a “premium service” that could compete with CMC for riders.

As for a history of CSL, it would be hard for anyone to better the Chicago Surface Lines book by Alan R. Lind, especially the third edition published in 1979.

The subject is of sufficient complexity to demand a series of books, of which Chicago Streetcar Pictorial: The PCC Car Era, 1936-1958 (published as Bulletin 146 of the Central Electric Railfans’ Association in 2015), at 448 pages, including several hundred photos in color, forms an important part. I am proud to have been a co-author of that book.

My upcoming book Chicago Trolleys, although a much more modest 128 pages, will be another addition to that field.

-David Sadowski

Bonus Pictures

FYI, I found this brochure in one of the issues of Surface Service (the Chicago Surface Lines employee publication) I recently scanned:

Pre-Order Our New Book Chicago Trolleys

On the Cover: Car 1747 was built between 1885 and 1893 by the Chicago City Railway, which operated lines on the South Side starting in April 1859. This is a single-truck (one set of wheels) open electric car; most likely a cable car, retrofitted with a trolley and traction motor. The man at right is conductor William Stevely Atchison (1861-1921), and this image came from his granddaughter. (Courtesy of Debbie Becker.)

We are pleased to report that our new book Chicago Trolleys will be released on September 25th by Arcadia Publishing. You can pre-order an autographed copy through us today (see below). Chicago Trolleys will also be available wherever Arcadia books are sold.

Overview

Chicago’s extensive transit system first started in 1859, when horsecars ran on rails in city streets. Cable cars and electric streetcars came next. Where new trolley car lines were built, people, businesses, and neighborhoods followed. Chicago quickly became a world-class city. At its peak, Chicago had over 3,000 streetcars and 1,000 miles of track—the largest such system in the world. By the 1930s, there were also streamlined trolleys and trolley buses on rubber tires. Some parts of Chicago’s famous “L” system also used trolley wire instead of a third rail. Trolley cars once took people from the Loop to such faraway places as Aurora, Elgin, Milwaukee, and South Bend. A few still run today.

The book features 226 classic black-and-white images, each with detailed captions, in 10 chapters:

1. Early Traction

2. Consolidation and Growth

3. Trolleys to the Suburbs

4. Trolleys on the “L”

5. Interurbans Under Wire

6. The Streamlined Era

7. The War Years

8. Unification and Change

9. Trolley Buses

10. Preserving History

Product Details

ISBN-13: 9781467126816

Publisher: Arcadia Publishing SC

Publication date: 09/25/2017

Series: Images of Rail

Pages: 128

Meet the Author

David Sadowski has been interested in streetcars ever since his father took him for a ride on one of the last remaining lines in 1958. He grew up riding trolley buses and “L” trains all over Chicago. He coauthored Chicago Streetcar Pictorial: The PCC Car Era, 1936–1958, and runs the online Trolley Dodger blog. Come along for the ride as we travel from one side of the city to the other and see how trolley cars and buses moved Chicago’s millions of hardworking, diverse people.

Images of Rail

The Images of Rail series celebrates the history of rail, trolley, streetcar, and subway transportation across the country. Using archival photographs, each title presents the people, places, and events that helped revolutionize transportation and commerce in 19th- and 20th-century America. Arcadia is proud to play a part in the preservation of local heritage, making history available to all.

The book costs just $21.99 plus shipping. Shipping within the US is included in the price. Shipping to Canada is just $5 additional, or $10 elsewhere.

Please note that Illinois residents must pay 10.00% sales tax on their purchases.

We appreciate your business!

For Shipping to US Addresses:

For Shipping to Canada:

For Shipping Elsewhere:

NEW – Chicago Trolleys Postcard Collection

We are pleased to report that selected images from our upcoming book Chicago Trolleys will be available on September 25th in a pack of 15 postcards, all for just $7.99. This is part of a series put out by Arcadia Publishing. Dimensions: 6″ wide x 4.25″ tall

The Postcards of America Series

Here in the 21st century, when everyone who’s anyone seems to do most of their communicating via Facebook and Twitter, it’s only natural to wax a little nostalgic when it comes to days gone by. What happened to more personal means of communication like hand-written letters on nice stationery? Why don’t people still send postcards when they move someplace new or go away on vacation?

If that line of thinking sounds familiar, then Arcadia Publishing’s Postcards of America was launched with you in mind. Each beautiful volume features a different collection of real vintage postcards that you can mail to your friends and family.

Pre-Order your Chicago Trolleys Postcard Pack today!

For Shipping to US Addresses:

For Shipping to Canada:

For Shipping Elsewhere:

Help Support The Trolley Dodger

This is our 190th post, and we are gradually creating a body of work and an online resource for the benefit of all railfans, everywhere. To date, we have received over 307,000 page views, for which we are very grateful.

You can help us continue our original transit research by checking out the fine products in our Online Store.

As we have said before, “If you buy here, we will be here.”

We thank you for your support.

DONATIONS

In order to continue giving you the kinds of historic railroad images that you have come to expect from The Trolley Dodger, we need your help and support. It costs money to maintain this website, and to do the sort of historic research that is our specialty.

Your financial contributions help make this web site better, and are greatly appreciated.

I think there is something involved here that nobody likes to bring up. CRT was in many ways a very backward operation. The fleet was mostly wood, except for the 455 cars used exclusively on the subway routes (Howard-Ravenswood-Englewood-Jackson Park. Otherwise you were looking at 1910. All cars had manual gates, so an 8 car train had 8 trainmen. New York had converted a large part of their fleet to multiple-unit door control in the 1930’s, so an 8 car train only needed 4 trainmen. But this cost a thousand or so dollars a car, and CRT simply did not have the money, even though it would have saved an enormous amount in the long run. Second, the city and state had been pressuring CRT to replace wood cars since the 1936 Granville wreck, but nothing could be done, because, again, the CRT had no money. Best they could do was “reinforce” all-wood cars by drilling a couple of holes thru the frame the length of the car and inserting old rails that would, I suppose, help somewhat in keeping the frame from collapsing in a collision. But in any event, CRT was a physical mess, and unable to do anything about it.

Now along comes CTA. CTA had access to money, but since it had no taxing authority (a huge long-term error when setting up the agency, as it turned out). As soon as CTA took over, the city and state really started turning up the pressure to do something about the wood L cars. A couple of early wrecks did nothing to help the situation. CTA did, however, start ordering new cars, the 6000’s. The first two batches (6001-6130 and 6131-6200) were all-new, but by the time the third group as about to be ordered, it was starting to dawn on CTA that all-new cars were going to be too expensive in the quantities needed. So bids were asked for 270 all-new or 270 “rebuilt” cars using basically everything except the carbodies of PCC’s. The “rebuilt” bid came in much lower than all-new, and SCL got the order for 6201-6470, with 270 Pullman PCC’s “traded-in”. CTA apparently never really liked the Pullmans, supposedly because they were heavier than the St Louis cars and were seen as excessive power users and track wreckers. However, note that the Pullmans and St Louis exchanged trucks before being shipped off, as at the time it was thought the B-3 trucks were unable to run at over 50mph for extended periods of time.

So basically the PCC’s were sacrificed to save the L system. Otherwise, most likely only the North-South would have survived, with the Met and lake St having to be abandoned for lack of cars, with Ravenswood meeting its end also to provide cars to open the Dearborn Subway, which after all had been sitting there since 1939 or so, ready to be completed and opened, but with nothing to run in it.

The other problem was the condition of the tracks. There was a lot of bad track by the 1940’s in the streets. CSL had done a huge amount of track rebuilding in the 1908-1928 period, but not much after that, so track was starting to fall apart by the 1940’s. CTA was forced to do track jobs as late as 1955 because in places the tracks (and thus the street) had become nearly unusable. The old Chicago Sun-Times had a “bad track photo of the day” feature every day in the early 50’s showing atrocious potholes on streetcar tracks. The city was again putting more and more pressure on CTA to get rid of streetcars so the streets could be repaved. For instance, within a couple of months after Madison was converted, mostly due to the street falling apart west of Pulaski, there was a nice pair of photos in the Sun-Times showing a badly decayed street “before” and a freshly paved street at the same spot “after”. (Note, too, that in several places, Madison being one, only the two middle lanes with the tracks were repaved, the outside lanes not needing repaving until 20 or more years later!). This was an era when car ownership was skyrocketing, and if you do not think people loved freshly paved streets with no tracks, you would be truly mistaken.

So in conclusion, several unconnected issues forced what was inevitable. There was no way CTA could keep both the L and the streetcars going. One had to go to save the other.

I have also been told that the Pullman PCCs, with their GE motors and control equipment, were much more problematic than the Westinghouse-equipped St. Louis cars. When the Pullmans were “traded in”, the new 6000s made from them received Westinghouse accelerators, but retained all their previous GE motors and electrical equipment, and the veteran “L” shopmen I’ve known all detested the GE equipment.

Internally, the CTA cited labor cost during the 1950ss as being the main reason for eliminating streetcars. They wanted to replace two-man streetcars with one-man buses. However, one-man PCCs would have had lower labor cost than buses, since they had greater capacity (CTA estimated it would take 1.5 buses to replace a streetcar.)

One other thing that tipped the scales heavily in favor of the rapid transit lines was the February 1951 opening of the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway. This was a tremendous success and a great improvement over the Met “L” route it replaced, which did not take a direct path downtown.

As for the PCC Conversion Program, the sale of PCCs to St. Louis Car Company was handled as a separate transaction from CTA’s purchase of new railcars. SLCC gave CTA $11k for each of 570 PCCs, but since there were additional costs involved with reconditioning parts, starting with adapting the controllers, this resulted in thousands of dollars in additional costs which were rolled into how much CTA paid for each 6000.

Therefore, only the income from the sale of the PCCs was detailed, and not the costs, which were said to have increased over time, as parts needed more reconditioning. By the end of the program (last order was placed in 1958), CTA admitted that they were getting no more than scrap value for the cars.

But by then, it didn’t matter, since the last wooden “L” cars were taken out of service in late 1957.

Even with all these maneuvers, during the first decade of CTA operation, the rapid transit system contracted by about 25%, with the elimination of Niles Center, Westchester, Humboldt Park, Normal Park, Kenwood, and Stockyards, and the cutback of Douglas.

CTA’s first idea regarding the PCCs was to ship one car each to SLCC and Pullman to see if the bodies could be converted into rapid transit cars. This was not feasible.

A contract was awarded to SLCC in 1952 for new 6000s with some PCC parts, but this contract had to be cancelled in early 1953, and the matter put out to rebid. This earlier contract was the source of some of the inflated savings that were claimed for the program.

The remaining contracts for 6000s only had one bidder (SLCC) as for some reason the CTA considered Pullman’s original bid to be non-competitive. This means that each of the various contracts that followed only had one bidder– the specs were worded in such a way as to make it practically impossible for anyone other than SLCC to win the contract.

To go into the matter further, I will need to compare how much the per-car cost of the 6000s increased over time, indexed for inflation.

As I think about it, Speedrail’s acquisition of PCC cars might actually have acted against their best interests at the time.

As we know, Speedrail was entirely dependent on Cold Spring Shops for any major maintenance beyond the “terminal inspection” level. They could not do major repairs (like motor changes) at the Public Service Building, and they had no other heavy repair facility at hand, even though Maeder indicated that he wanted to build one. I have long thought that, had they been so inclined, TMER&T could have sunk Speedrail fairly quickly by simply denying them maintenance and letting attrition do the rest.

As it was, while it may have been a bit of a nuisance for Cold Spring to accommodate Speedrail (interruption of their regular shop workflow, special accounting for an outside “customer” rather than simply billing charges to the usual expense accounts, et al.) it was not an issue for them to do the work, practically speaking. Speedrail’s lightweight cars used conventional old-school equipment, trucks, and body design that the Shops were already familiar with, and in most cases had parts for them already on hand.

PCC technology is a whole different ball game, and Cold Spring would not have had the personnel, maintenance equipment, or parts on hand to accommodate it. Likewise, it wouldn’t have made economic sense for TMER&T to either invest in the related maintenance equipment or send its people off to learn PCC technology for one “outsider”…especially one in a decidedly sketchy financial condition. Speedrail’s acquisition of PCC cars, while still being dependent on Cold Spring, would have given TMER&T legitimate reason to say “sorry, we can’t help you here” and cut off their maintenance services.

Regarding whether Ralph Janus was part of the 1121 freight crew on 9/5/50, I believe there was a subsequent “finding of fault” article that named all three crewmen a few days or weeks after the initial article about the collision. I would look it up myself, but researching the Milwaukee papers from Chicago has become a good bit more difficult now that their digital archives have been removed from Google News to a subscription service.

Regarding double-ended PCCs: San Francisco Muni and Illinois Terminal’s Granite City suburban operation also had them.

M did not have turning loops on any of the streetcar lines and that is part of the reason S.B. Way was not interested in buying PCC’s for Milwaukee. It would have meant constructing loops at the ends of the car lines or buying double ended PCC’s.

There were a few loops in the Milwaukee system; one at east side station, east North Ave., at 35th and Fond Du Lac Ave., at N.27th st. & Hopkins. and a loop at the C&NW RR’s lakefront station serving east bound Wisconsin Ave and Michigan St. lines, most of the route numbers that served Wisconsin Ave. had loops at either end often using the Fond Du Lac and Hopkins loops. The key reason that TMER&L Co was not interested in the PCC was their costs of track maintenance.

Curiously, TMER&LCo was an original member of the ERPCC committee, seems their interest was that possibly the ERPCCC might just come up with some technology that TM could upgrade it’s existing fleet of late 1920s designed cars.

[…] photos that I bought recently. I purchased about 30 photos, some of which were included with my Railroad Record Club Treasure Hut story (see our post from July 30, 2017), here are the […]

[…] Dodger Mailbag, 10-31-2016 Iowa Traction (December 6, 2016) An Interurban Legacy (March 4, 2017) Railroad Record Club Treasure Hunt (July 30, […]

[…] can find Part 1 here: Railroad Record Club Treasure Hunt (July 30, […]

I was very impressed with the series of reports about the RRC.

I’m a railfan lives in Japan, and I was looking for railroad vinyls and ended up here. There are many of them in Japan, and they are all great I think. So I became interested in foreign sounds and was looking into USA vinyls.

Thanks to your great efforts and sacrifices, I have gained a lot of knowledge.

I wrote a comment just to say thank you.

But I’m sorry for my poor English.

And I hope you can continue these projects.

I am glad we could be of service.